The house on Massachusetts Avenue in Upper Darby had been sitting on the market for a while when Tim Miles and his wife bought it for $185,000 last year.

The annual bill for the two-story house on a sixth of an acre was more than $10,500. The township has some of the region’s highest taxes, but Miles’ property levy was thousands of dollars higher than even those on comparably priced homes in the township.

The reason: The county estimate of the home’s worth — the “assessment” on which the tax bill is based — was too high.

Why? Years or decades pass between countywide reassessments, leaving many property owners to pay more than their fair share — or less. Delaware County’s are so out of whack that a judge has ordered the county to revalue all its properties.

Helping the Neighbors

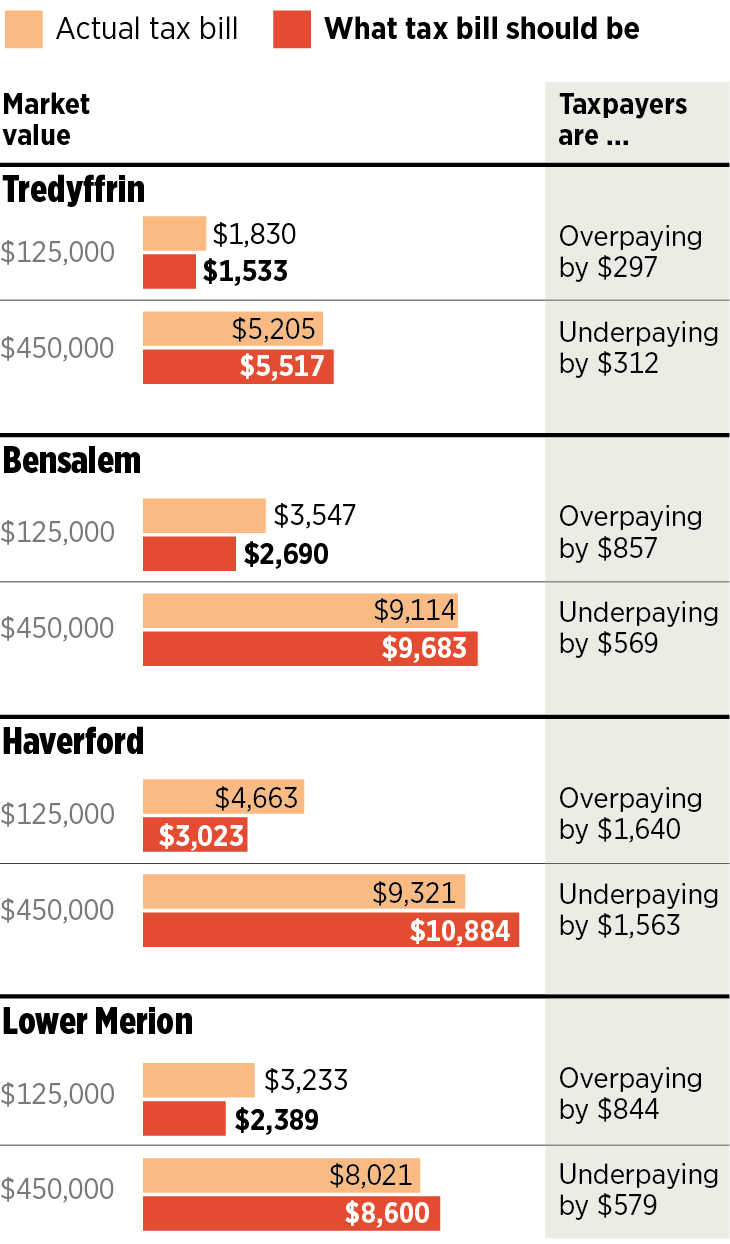

All told, in Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties, more than 210,000 homeowners could be overpaying their taxes, based on state standards, according to an analysis by the Inquirer and Daily News of sales and property records and state data. In effect, they are helping to subsidize the tax bills of roughly an equal number who are underpaying.

Chances are most homeowners don’t know it.

Property assessments are set by counties in Pennsylvania. Unlike some other states, the state does not require regular reassessments. The International Association of Assessing Officersrecommends they be done every year.

In New Jersey, revaluations are conducted by towns, and more frequently. Philadelphia overhauled its system in 2013 and reassesses annually, primarily through computer analysis of recent sales. Not that property levies are beloved in the city or the Garden State.

But nearly two decades have passed since mass appraisals in Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties, and Richard Nixon was president the last time Bucks County did so. The result is a significant imbalance in the tax bills that pay for everything from teacher salaries to police protection to mosquito spraying. Property taxes also affect renters, because they are passed along in monthly bills.

Reassessments are costly — and political minefields that county officials would prefer to avoid.

In the meantime, counties annually submit prices and assessment ratios for all sales. The state then calculates an average — or common level — ratio for each county as a measure of fairness and to establish the appeal standard. For example, in Delaware County for this year the ratio is 61, meaning that a $100,000 house should be assessed and taxed based on $61,000 of value. The ratio in Chester County is 52.9; it’s 54.1 in Montgomery. Because it’s been 45 years since reassessment in Bucks, the ratio is only 10.9.

The flaw in the system is obvious: Communities within a county don’t evenly rise or fall in value. Delaware County, for example, spans 190 square miles, from the rough streets of Chester to the upscale homes of Newtown Square. Struggling towns’ properties lose value over time while market values increase in wealthier communities, or they can rocket if a town suddenly becomes hot.

The result: Even when using the ratio system, many assessments are too high or too low.

Between countywide revaluations, assessments change only if an owner appeals or builds an addition. Newly constructed homes receive fresh assessments.

Don Weiss, a Delaware County-based lawyer who represents clients in assessment appeals, said the system is not only unfair for taxpayers — it’s also difficult for them to understand. Tax bills don’t include the market value, and it is left to the homeowner to figure it out. In New Jersey and Philadelphia, the assessment is supposed to match the value.

“If the people in Harrisburg, if they would get a clue, they would put down that every county at the very least has to put on their tax bill what the real value is, not just the assessment,” he said. “It’s a terrible situation throughout the whole state.”

Up and down in Delco

In Delaware County, where a court-mandated reassessment is about to begin, more than one-third of homes are overassessed, and nearly one-third of homeowners are paying too little in taxes because their assessments are too low, according to the Inquirer and Daily News analysis.

Some of the county’s economically struggling towns — Upland, Darby, and Marcus Hook Boroughs — are among the most overassessed municipalities on average. Radnor and Haverford Townships and Media Borough are the most underassessed.

Low Income, High Tax Rate

The figures aren’t quite as bad in the neighboring counties, but more than 20 percent of homes in Montgomery and Chester Counties are overassessed, while 16 percent of Bucks County homeowners are paying too much, and roughly a third are paying too little.

Although the system might be confusing, modern times do offer some advantages. Online public records and commercial websites such as Zillow and Trulia offer a trove of data in just a few clicks.

“Sometimes you look at your neighbors and what they’re paying in taxes and it drives you crazy,” Robert Adshead, a member of the Montgomery County board, explained to one homeowner at an appeals hearing this year. “There’s a million reasons why that could happen.”

Order from the court

Lenore and James Kaufman were among the homeowners whose assessment appeals moved a Delaware County judge to order a countywide reassessment this year.

The Rose Valley couple bought their home in the Traymore development in 2014 for $721,000. Their newly constructed three-bedroom home came with an annual tax bill of more than $36,000. After their successful appeal, their tax bill was reduced by more than $11,000 per year.

Their situation is a common one for owners of newly constructed homes in every county. New construction is hit with the going ratio at the time the property is sold. The assessment on a new home purchased in 2014 is likely to carry a significantly higher ratio than on one bought in 2000. Neighbors in older homes often reap the benefits.

Delaware County approved a $6 million contract earlier this month for its reassessment. Marianne Grace, the county’s executive director, said it will involve using computer data, taking aerial photos of properties, and making some door-to-door visits. Homeowners will have a year to appeal their new assessments before they go into effect.

Over- and Underassessments in Delaware County

Chester, Bucks, and Montgomery Counties have no similar plans, officials said. However, both Chester and Delaware Counties were ordered to reassess in the 1990s, and Montgomery County eventually did the same.

Bucks County, which has the lowest percentage of overassessed homes in the four counties, has remained a holdout. County officials say the levels of any assessment inaccuracies haven’t been a problem. “It doesn’t make sense for us to spend $10 million or $15 million of taxpayer money to resolve an issue that really doesn’t exist on the average,” said David Boscola, director of finance and administration for Bucks County.

Relatively few properties end up being assessed right at the county ratios, and assessments vary among towns and neighborhoods. In many cases, property owners who paid similar amounts for similar homes in the same town can have vastly different tax bills.

When homeowners appeal, they must present county boards with sales information for comparable homes to make a case that the county’s market value overstates the value of their houses.

Boards of assessment appeals in Bucks, Delaware, Montgomery, and Chester Counties heard more than 4,300 appeals this year — from homeowners with mobile homes to those with mansions.

Some taxpayers compare their tax bills with their neighbors’ and think they must be paying too much if their neighbors pay less, which is a “big misconception,” said Betty Jane McCardell, chair of the Chester County board. “We compare market value, not assessments.”

Susan Callahan, a grant writer for the Moyer Foundation children’s charity, and her husband, Norman, a doctor, knew they were probably paying too much in taxes on their Easttown Township home. But it was one of those things they never got around to addressing, even as they got the occasional letter in the mail from lawyers saying they could be eligible for lower bills.

“You’re never really sure if that’s something that’s legitimate,” said Susan Callahan, 54, who bought her home 15 years ago for $720,000.

Her Realtor and friend told her recently she would never be able to sell her house in the future if she didn’t do something about her property taxes.

A few hundred dollars for an appraisal, and a five-minute tax assessment appeal hearing later, and the Callahans will pay roughly $3,600 less in taxes next year. Their house’s assessment dropped by $118,720.

“If I’d known it was that simple, I would have done it sooner,” Callahan said.

Jack Nash, who lives in Montgomery County, knew the system before he appealed his property assessment this year.

He is a certified appraiser, and he often appears before the appeals board on behalf of clients who own commercial properties. But this fall, he came to talk about his own home in New Hanover Township.

Nash purchased his home for $241,445 in 1999 and has tracked the county ratios closely. Finally, this year he saw a window of opportunity for appeal.

“Every year, that ratio comes out in June and the first thing I do is — I don’t go to any of my clients’ tax bills — I go to my tax bill,” Nash said. “For 10 years I’ve been looking at it and finally it was like, it’s time.”

He appeared before the board in October, and heard a few weeks later that his assessment would be lowered. Nash will save about $700 in taxes next year.

Remedies

In response to lawsuits through the years challenging the fairness of the state’s property assessment system, a legislative task force formed a year ago to address the issue.

“We want taxpayers to feel the process is fair and they understand how it’s done,” said State Rep. Kate Harper (R., Montgomery), a member of the task force.

It also is developing a “self-assessment tool” with objective criteria that county assessors and taxpayers can use to compare counties and figure out whether reassessment is needed, Harper said.

Inequities in assessments also have served as a rallying cry for Pennsylvania residents who would like to limit or eliminate property taxes.

Other critics of the system have suggested mandating regular reassessments, or requiring them once a county’s ratio reaches a specific number.

“What Pennsylvania needs is … cyclical assessments,” said Robert P. Strauss, a professor of economics and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University.

While they wait for elusive reform, Kay Mooney of Fox & Roach and her fellow real estate agents keep close track of assessments when advising clients.

“When I get a call from somebody, I immediately pull up their tax records and see what they’re paying,” Mooney said.

“Lots of times, they have no idea they’re paying more than somebody else.”

Leave A Comment